An alternative to Decentralized Web

The Internet was born decentralized: its fundamental networking protocols such as TCP/IP as well as application layer standards like the Web or Email were created so that there is no central authority in charge.

Yet, by now we have almost completely lost sight of that idea. I recently noticed that 96% of the emails my company sends are opened in the Gmail client. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are running half the web through their cloud infrastructure, and Facebook hijacked the social interactions of billions.

It's not surprising that demand has arisen to take back (or rather, dismantle) control and return to the native values of the Internet. A collection of these new proposals has been referred to by the umbrella term Decentralized Web (or sometimes Distributed Web) or Dweb. What is Dweb?

Decentralized Web

A 2018 article published in The Guardian titled Decentralisation: the next big step for the world wide web sums it up well: “The DWeb is about re-decentralising things — so we aren’t reliant on these intermediaries to connect us. Instead users keep control of their data and connect and interact and exchange messages directly with others in their network.”

In recent years a number of exciting projects have emerged: PeerSon, Safebook, SuperNova, PrPl, Vis-a-Vis, Diaspora, Mastodon, Scuttlebutt, etc. Dweb is more than just online social networks, but most of the academic and open-source effort — understandably—goes into OSNs. OSN here is a term used broadly and it encompasses everything from microblogging through instant messaging to photo sharing. There are two typical architectures: peer-to-peer and federated services (some services implement a mix of these).

In the peer-to-peer architecture users themselves directly share content with each other, typically from devices they own (e.g. smartphones, home computers). Sometimes metadata is stored in a different tier (PeerSon, Safebook) and is propagated throughout the network e.g. as a Distributed Hash Table. Some data might be cached in other nodes. There are no "servers" in a conceptual sense, everyone serves their own data.

Federated services differ from peer-to-peer networks in that there’s a significantly smaller number of nodes than users on the network, and a node hosts many user accounts. The user selects a server when signing up to the service and only communicates with that server in the future, but all servers communicate with each other in a decentralized federation. Perhaps the most successful DOSN, Diaspora, offers the same architecture, where anyone can host a "pod" and user data is propagated across the network of pods.

This type of architecture is similar to some older successful protocols, like SMTP (emailing) or XMPP (instant messaging).

The problems

“Decentralization is undoubtedly one of the inherent solutions to major offline privacy issues in OSNs; however, it does not come free of new challenges and issues to privacy itself.” — summarizes the author of Challenges in the Decentralised Web: The Mastodon Case. The study lists a number of privacy and fraud-related issues with one popular Dweb microblogging service, Mastodon. In a 2017 paper titled Decentralized privacy-preserving services for Online Social Networks the authors describe a number of problems with decentralized online social networks:

- Performance is poor and availability is limited

- Access control becomes complicated

- Data replication poses privacy concerns

- Collaboratively owned content is difficult to implement

- Identity management, content moderation, and fraud prevention are difficult to impossible

Another issue is the lack of a business model. “All of the DOSN proposals except SuperNova adopt the voluntary business model. In the voluntary model, a user either stores content in the leased node […] or participates using his/her personal machine […]. There is no monetary incentive involved in participation” (Chowdhury, 2014). This is a problem because some crucial OSN features do in fact require a functioning business model.

The elephant in the room is content moderation. It’s a large cost element of traditional social networks and it cannot be (fully) automated nor distributed. Without effective (and costly) moderation DOSN’s are destined to the ugly fate of Parler. No application platform or cloud service will risk getting associated with neo-nazis or insane conspiracy theorists.

Moderation aside, Dweb solutions without a business model are limited in popularity to the number of industry enthusiasts, because they cannot market their products effectively and will be outcompeted by centralized, for-profit organizations.

Distribute the infrastructure

Generally speaking, control, a functioning business model, and having (parts of) the service centralized are not necessarily evil things and could benefit the users of the service.

Can we find a middle ground? Maybe.

From social networks to cloud email solutions, from smart home devices to cloud file storage services, nearly all online services operate under the following assumption: the service and the underlying infrastructure are indivisible.

When a user signs up to a social network such as Facebook or starts using a cloud email service such as Outlook.com, they implicitly accept that by using the service itself, they commit to the underlying infrastructure operated by the same entity that runs the service (or sells the hardware if it's a cloud-connected gadget like a security camera). In other words, when you upload your photos to Instagram, for example, you commit to using Instagram’s servers to store and serve them.

I argue that it's not inherently impossible to separate the infrastructure from the service.

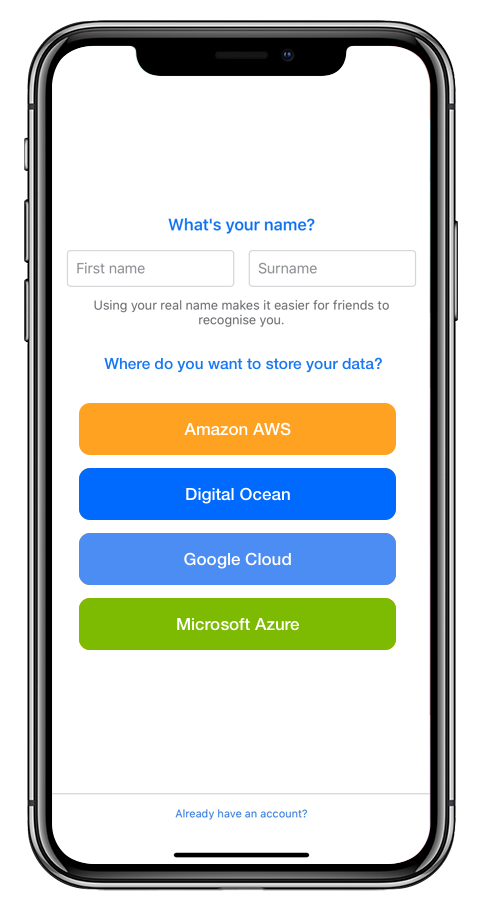

What if you could choose where your data is stored, you'd be able to see it in its entirety, and revoke access any time? What if you saw this screen when you sign up for Facebook?

The same goes for your email provider, your security camera, your photo backup, your wearables. You choose the underlying storage (and perhaps transmission) infrastructure and you have full control over it.

Separating the infrastructure from the service and giving control to the user over their data potentially enables data portability — moving to another service together with all your data effortlessly. Controlling the storage infrastructure means that the personal data of the user cannot be held hostage.

Challenges and caveats

One obvious challenge comes from the structure of the data: service providers might use their own proprietary formats, database schemata, etc. to store your personal data. Moving e.g. from Google Drive to Dropbox might be challenging because of the different data formats used by both. However, it’s not difficult to imagine that services will appear on the market that, given access to the complete data the user now controls, can “translate” from one to another. It’s also easy to envision that services themselves (Dropbox in this example) would reverse-engineer data formats of their competitors and offer to translate them while keeping the personal data on the storage chosen by the user.

It does not stop there. Access to the raw and complete data enables a plethora of different services — paid or free, proprietary or open-source — that analyze, visualize, clean, search, and share the data, further increasing the visibility, utility, and control of the data subject. Once you have access to your full data (and not just its "shadow" the service provider lets you see), your opportunities are endless.

Another challenge is adoption: It's hard to imagine tech giants such as Google or Facebook voluntarily giving up on their ownership of (part of) the infrastructure of the services they offer. Even if they do, they might copy or "cache" your data in bad faith while they have access to it and be reluctant to "forget it". But it's not impossible to envision new kinds of regulations in the future that get them to do both. In fact, GDPR already has several sections closely regulating the storage of your personal data (retention length, secure storage, right to access, right to data erasure, right to portability). Decoupling the infrastructure from the service takes care of several of those points in an elegant way.

Pricing of the storage services remains an open question. Not everyone will be willing to pay for the hard disk and bandwidth they used to get for free, even with all the potential benefits. Some infrastructure providers might subsidize services for some access to the data. Some ISPs might offer storage as part of the package. The point is that the choice of provider is given to the user.

Some of the challenges are technical. The dispersed nature of data in this setup is a non-issue for some types of services (e.g. photo backup, security camera) but might prove challenging for some others (e.g. social networks). Yet, I believe these challenges aren't impossible to solve and none of the issues are fundamental.

Conclusion

Dweb is fascinating, but there's a risk that it will remain an idealistic fever dream of a few enthusiasts. Some things require central control (maybe even Siren Servers) and a functioning business model. That doesn't mean we have to give it all up.

The idea in this article doesn't solve all the issues brought upon us by our tech overlords but it has the potential to improve privacy and increase control over our data. While the proposal is technical in nature, it has the capacity to form part of a legislative solution, an attribute missing from most Dweb projects. In that, it is akin to one of the most effective duos of regulation and engineering, one that drastically reduced fatal car accidents: the three-point seatbelt and the law that mandates its use.

The above article is a highly condensed version of a paper I wrote during my studies at the University of London.